FEATURE

In a recent article for The New Yorker, Nicholas Lemann examined the current zeitgeist for city living, underscoring the reality that as America creeps steadily towards cultural homogenization cities are among the last bastions of multiplicity. Their superficialities (demographics and facades) may ebb and flow, but the inherent value of cities is that they are petri dishes of humanity. A desire to comprehend and capture this humanity can perhaps explain the magnetism of the photographs of Vivian Maier.

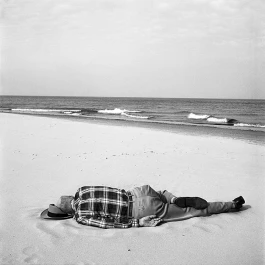

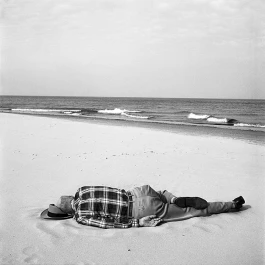

A nanny by trade, Vivian’s photographs were discovered nearly concurrent with her death in 2009 and depict post-war 20th century urban America. Beyond their innate beauty, what is most striking about the photographs is their timelessness. Aside from era-specific attire, their subject matter reflects everyday streetscapes and interactions that persist today in urban centers around the country, if not the globe.

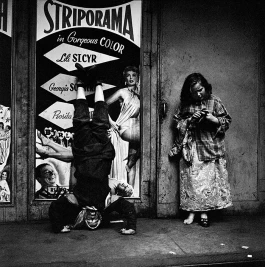

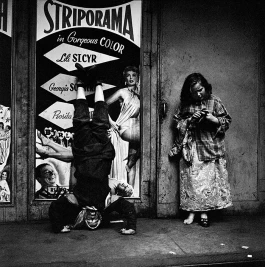

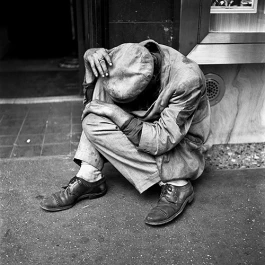

It is possible that Vivian was so apt at capturing the banal struggles, poetic moments and general oddities of city life with such startling authenticity because they made up the foundation of her own reality. Born in New York on February 1, 1926, Vivian spent her childhood between France and the United States, eventually settling in America. One could hypothesize that her international upbringing attuned her to universal human rituals that, interwoven in various wefts, create the fabric of a culture — or the moments captured in her photographs: a family’s twilight stroll, a pigeon’s flight, the bizarre antics of sidewalk showmen or the bereft fringes of society.

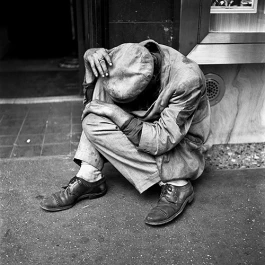

From 1951 through the 1990s, Vivian documented the rawness of urban existence. First in New York City and then in Chicago, she recorded an enduring world where the suburban bubble is stripped of its aspiration and replaced with a primitiveness that cannot be veiled behind a concrete veneer or picket fence, and where it is impossible to dream too big or too small — but it is also sometimes impossible to dream. Her images appear jarringly devoid of judgment, yet they are far from sterile. Perhaps she was validating her own eccentricities by documenting those of others. Accounts of past employers detail a Mary Poppins-type figure perpetually dressed in a uniform of men’s coats, felted hats and utilitarian shoes, with a Rolleiflex camera ever around her neck. Others depict her as a wildly private packrat who bordered on obsessive.

Maybe photography was her way of immortalizing what she seemed to view as her fleeting moments on earth. She took numerous self-portraits, and an audiotape found among her possessions discloses her stating, “I suppose nothing is supposed to last forever. We have to make room for other people. It’s a wheel. You get on you have to go to the end. And then somebody has the same opportunity to go to the end and so on. And somebody else takes their place.”

It could be that Vivian simply dared to stare when others looked away. Her brazen documentation of some of the more dejected states of human existence supposes a loner resistant to the societal norms that cause so many to turn a blind eye.

From what little is known of Vivian, any, all or none of these explanations could begin to rationalize her motivation for spending every free day taking and then vigilantly safeguarding more than a hundred thousand photographs, which were uncovered when young Chicago real estate agent John Maloof bought a box of negatives at an auction in 2007. After storing the box for nearly two years, John eventually began examining his purchase.

Ultimately locating Vivian’s name on a photo lab envelope, he googled her only to find an obituary from just a few days prior. More than two years on, working four to five days a week with a friend, John is still several years from developing and scanning all of Vivian’s work — a third of the negatives never made it beyond the film roll.

In her essay “On Keeping a Notebook,” Joan Didion explains her own creative tick, stating, “The impulse to write things down is a particularly compulsive one, inexplicable to those who do not share it, useful only accidentally, only secondarily, in the way that any compulsion tries to justify itself.” Perhaps the key to cracking the variously described “eccentric and delightful,” “strong and determined” code of Vivian Maier is this elementary: Photographs were her obsession, and their recently identified “usefulness,” merely accidental.

PUBLISHED IN DOSSIER

PHOTOGRAPHY BY VIVIAN MAIER

view more

FEATURE

In a recent article for The New Yorker, Nicholas Lemann examined the current zeitgeist for city living, underscoring the reality that as America creeps steadily towards cultural homogenization cities are among the last bastions of multiplicity. Their superficialities (demographics and facades) may ebb and flow, but the inherent value of cities is that they are petri dishes of humanity. A desire to comprehend and capture this humanity can perhaps explain the magnetism of the photographs of Vivian Maier.

A nanny by trade, Vivian’s photographs were discovered nearly concurrent with her death in 2009 and depict post-war 20th century urban America. Beyond their innate beauty, what is most striking about the photographs is their timelessness. Aside from era-specific attire, their subject matter reflects everyday streetscapes and interactions that persist today in urban centers around the country, if not the globe.

It is possible that Vivian was so apt at capturing the banal struggles, poetic moments and general oddities of city life with such startling authenticity because they made up the foundation of her own reality. Born in New York on February 1, 1926, Vivian spent her childhood between France and the United States, eventually settling in America. One could hypothesize that her international upbringing attuned her to universal human rituals that, interwoven in various wefts, create the fabric of a culture — or the moments captured in her photographs: a family’s twilight stroll, a pigeon’s flight, the bizarre antics of sidewalk showmen or the bereft fringes of society.

From 1951 through the 1990s, Vivian documented the rawness of urban existence. First in New York City and then in Chicago, she recorded an enduring world where the suburban bubble is stripped of its aspiration and replaced with a primitiveness that cannot be veiled behind a concrete veneer or picket fence, and where it is impossible to dream too big or too small — but it is also sometimes impossible to dream. Her images appear jarringly devoid of judgment, yet they are far from sterile. Perhaps she was validating her own eccentricities by documenting those of others. Accounts of past employers detail a Mary Poppins-type figure perpetually dressed in a uniform of men’s coats, felted hats and utilitarian shoes, with a Rolleiflex camera ever around her neck. Others depict her as a wildly private packrat who bordered on obsessive.

Maybe photography was her way of immortalizing what she seemed to view as her fleeting moments on earth. She took numerous self-portraits, and an audiotape found among her possessions discloses her stating, “I suppose nothing is supposed to last forever. We have to make room for other people. It’s a wheel. You get on you have to go to the end. And then somebody has the same opportunity to go to the end and so on. And somebody else takes their place.”

It could be that Vivian simply dared to stare when others looked away. Her brazen documentation of some of the more dejected states of human existence supposes a loner resistant to the societal norms that cause so many to turn a blind eye.

From what little is known of Vivian, any, all or none of these explanations could begin to rationalize her motivation for spending every free day taking and then vigilantly safeguarding more than a hundred thousand photographs, which were uncovered when young Chicago real estate agent John Maloof bought a box of negatives at an auction in 2007. After storing the box for nearly two years, John eventually began examining his purchase.

Ultimately locating Vivian’s name on a photo lab envelope, he googled her only to find an obituary from just a few days prior. More than two years on, working four to five days a week with a friend, John is still several years from developing and scanning all of Vivian’s work — a third of the negatives never made it beyond the film roll.

In her essay “On Keeping a Notebook,” Joan Didion explains her own creative tick, stating, “The impulse to write things down is a particularly compulsive one, inexplicable to those who do not share it, useful only accidentally, only secondarily, in the way that any compulsion tries to justify itself.” Perhaps the key to cracking the variously described “eccentric and delightful,” “strong and determined” code of Vivian Maier is this elementary: Photographs were her obsession, and their recently identified “usefulness,” merely accidental.

PUBLISHED IN DOSSIER

PHOTOGRAPHY BY VIVIAN MAIER

view more